Get ready, here comes some fringe pedantry that could very well be the difference in an interview, or the thing that saves you from hours of chasing a production bug!

I’m teeth-deep into the next season of The Imposter’s Handbook and currently, I’m writing about RSA, the cipher that powers SSH and is, evidently, the most downloaded bit of code in history.

I want to know the story behind this thing. Who came up with it, how it works, why it works, and will it keep working. So far, I’ve dug up one hell of a story. I’m not a crypto wonk, but I can see how people get sucked right into this field. I’m not really cut out for it, however, because little rabbit holes exist everywhere and I’m kind of like a magpie-rabbit: I chase shiny things down deep holes. I’m also super amazing with metaphors.

Anyway: last week I found out something weird that I thought I would share: mod and remainder are not the same thing. The really fun thing about that statement is that there are a small fraction of people reading this, jumping out of their chairs saying “NO SHIT I’VE BEEN TRYING TO TELL YOU AND EVERYONE ELSE FOREVER”.

Shout out to mods-not-remainder crew! This one’s for you.

What’s a Mod?

I had to look this up to, just like the last time the subject came up. It’s one of those things that I know, but don’t retain. When you “mod” something, you divide one number by another and take the remainder. So: 5 mod 2 would be 1 because 5 divided by 2 is 2 with 1 left over.

The term “mod” stands for the modulo operation, with 2 being the modulus. Most programming languages use % to denote a modulo operation: 5 % 2 = 1.

That’s where we get into the weird gray area: 1 is the remainder, not necessarily the result of a modulo.

Clock Math

I remember learning this in school, and then forgetting it. There’s a type of math called “Modular Mathematics” that deals with cyclic structures. The easiest way to think of this is a clock, which is cyclical in terms of the number 12. To a mathematician, a clock is mod 12. If you wanted to figure if 253 hours could be evenly divided into days, you could use 253 mod 24, which comes out to 13 so the answer would be no! The only way it could be “yes” is if the result was 0.

Another question you could answer would be “if I start on a road trip at 6PM, what time would it be when I get to my destination 16 hours later?”. That would be 6 + 16 mod 12 which is 10.

Cryptographers love mod because when you use it with really large numbers you can create what are known as one-way functions. These are special functions which allow you to easily calculate something in one direction, but not reverse it.

If I tell you that 9 is the result of my squaring operation, you can easily deduce that the input was 3 (or -3 as the case may be). You would have the entire process front to back. If I tell you that 9 is the result of my function mod 29, you would have a harder time trying to figure out what the input was.

Crypto folks like this idea because they can use a modulo with gigantic prime numbers in order to generate a cryptographic key. That’s a whole other story and you can buy the book if you want to read about it.

I need to stay on track.

Remainders and Clock Math

Now we get down to it: modulo and remainder act the same when the numbers are positive but much differently when the numbers are negative.

Consider this problem:

const x = 19 % 12;

console.log(x);

What’s the value of x? Some quick division and we can say there’s a single 12 with 7 left over, so 7 is our answer, which is correct. How about this one:

const y = 19 % -12;

console.log(y);

Using regular math, we can multiply -12 by -1, giving us 12, and we still have 7 left over, so our answer is 7 once again.

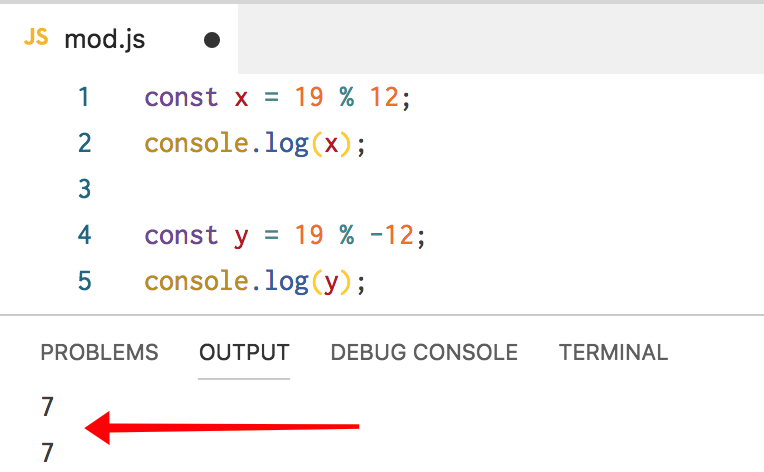

JavaScript agrees with this:

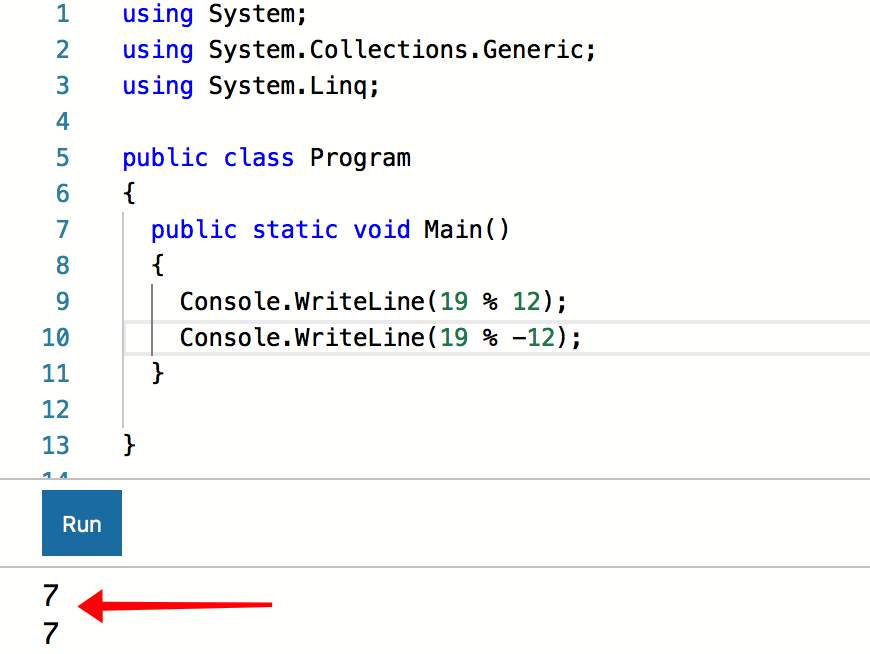

C# also agrees with this:

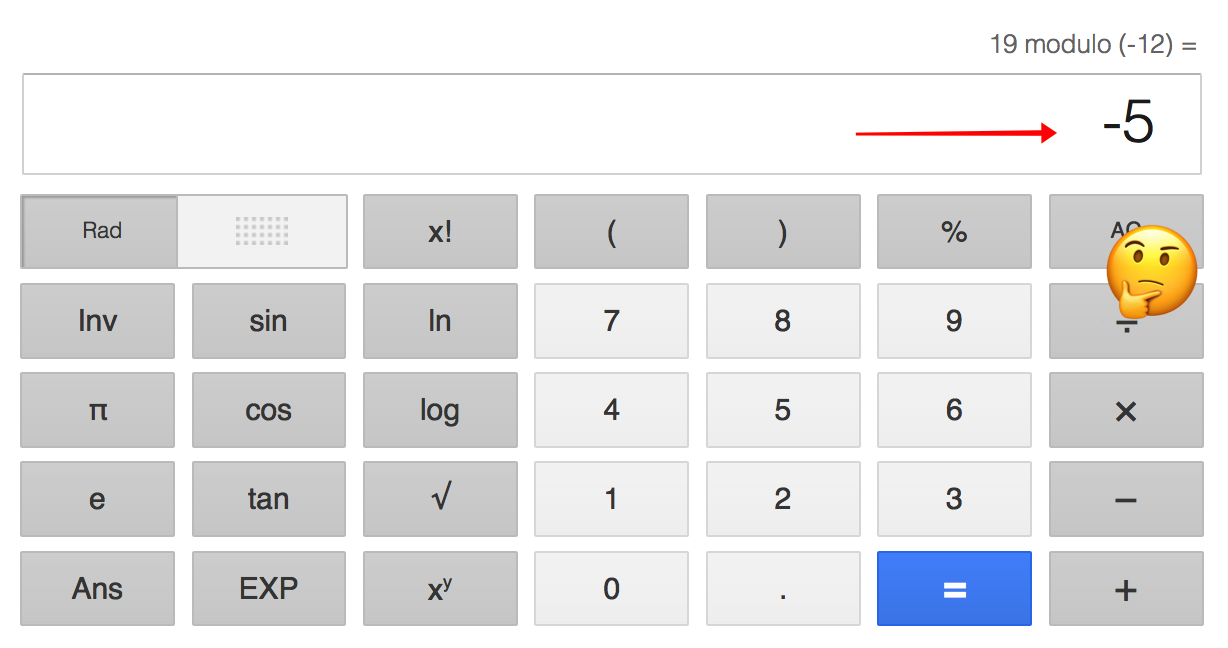

Google agrees with the first statement, but disagrees with the second:

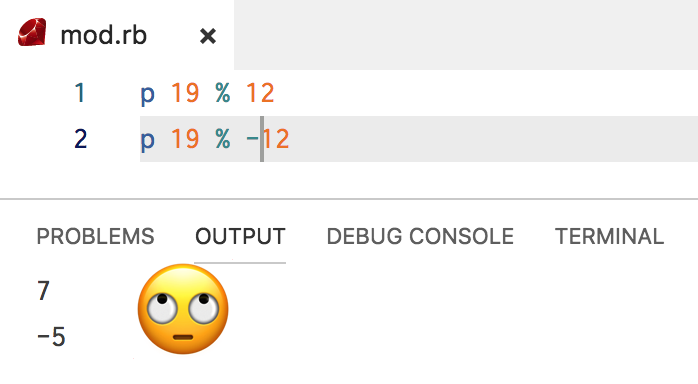

Ruby agrees with Google:

What in Djikstra’s name is HAPPENING HERE!

Spinning The Clock Backwards

The answer to this problem is understanding the difference between a remainder and a modulo. Programmers conflate these operations and they should not, as they only act the same when the divisor (in our case 12) is positive. You can easily send bugs into production if your divisor is negative.

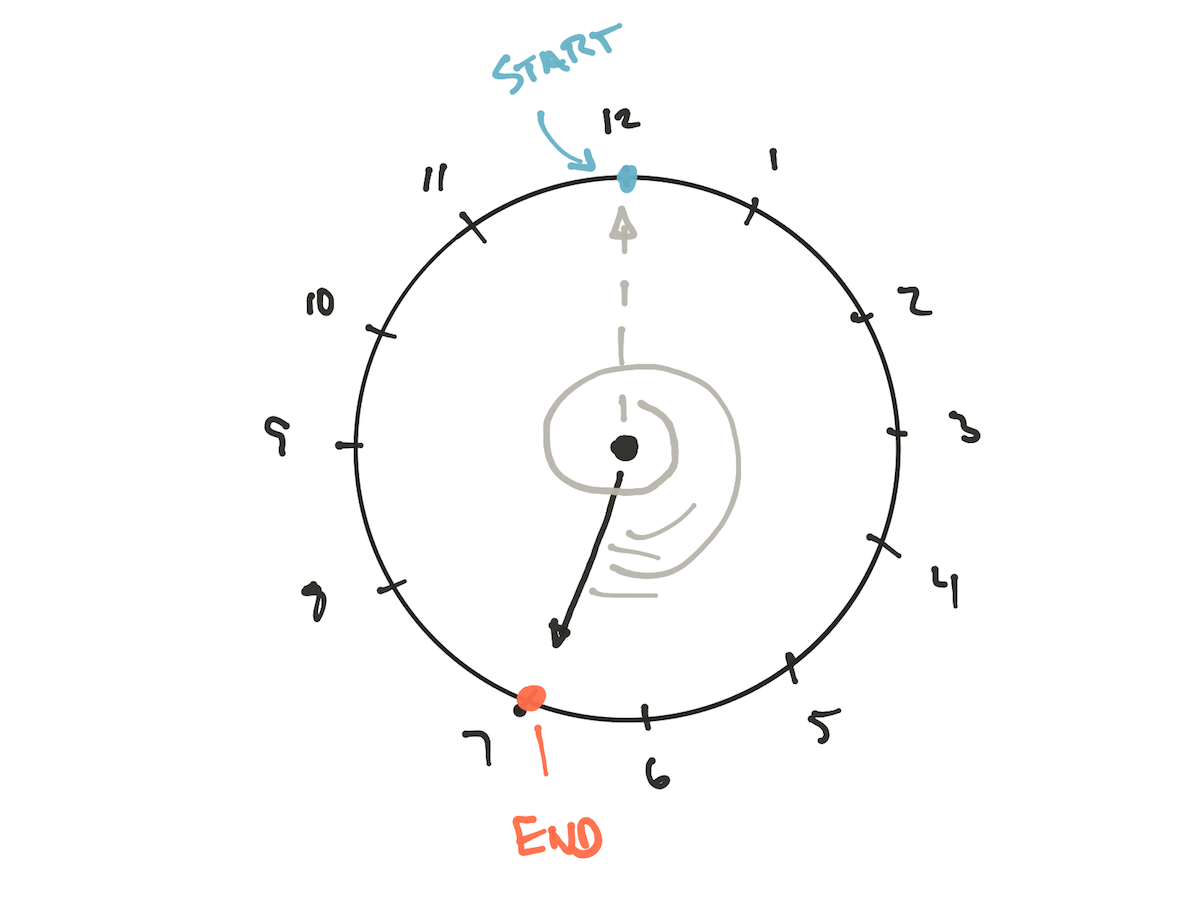

But why is there a discrepancy? Consider the positive modulo 19 mod 12 using a clock:

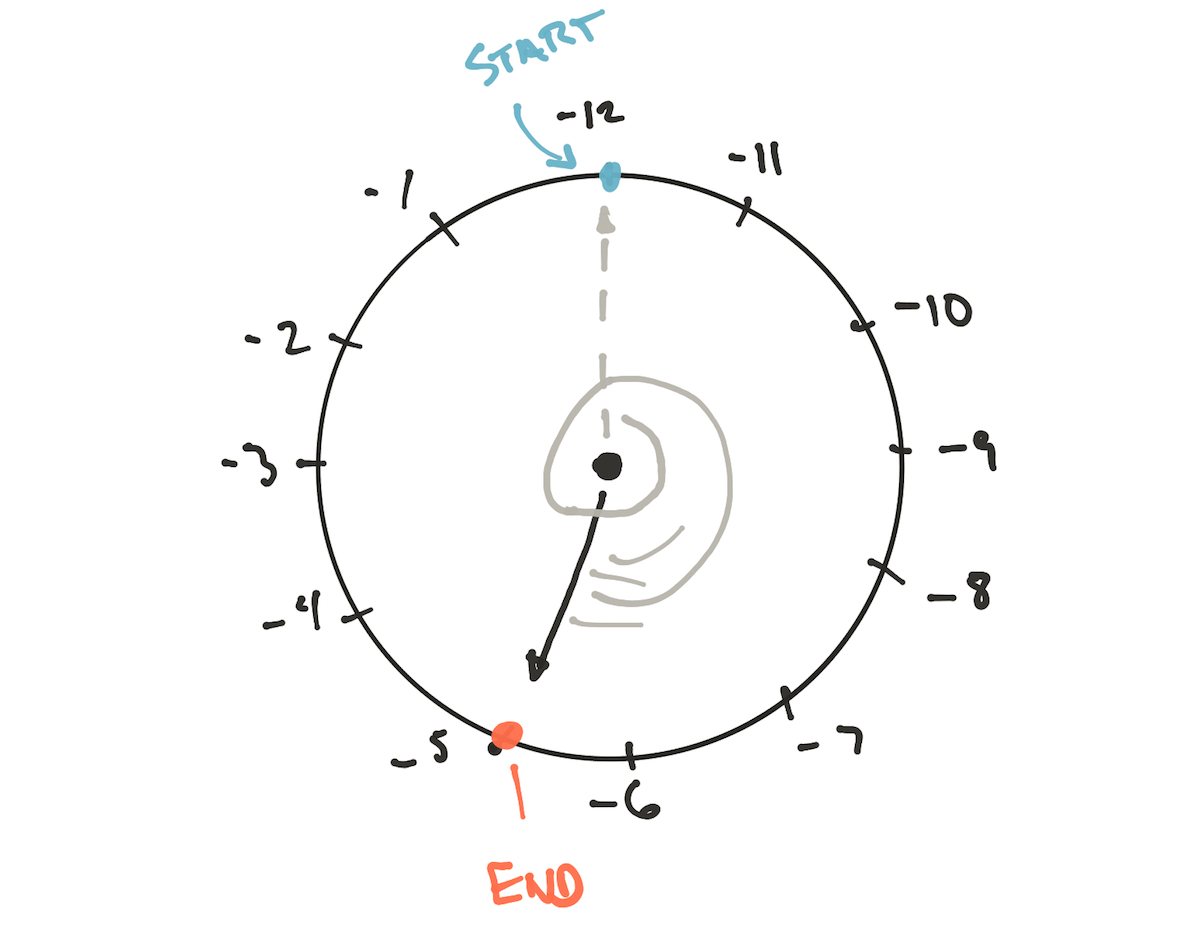

The end result is a 7, as we know, and we can prove this using some math. But what about 19 mod -12? We have to use a different clock:

Our modulus is -12, and we can’t ignore that or change it by multiplying by -1 as that’s not the way modular math works. The only way to calculate this correctly is to relabel the clock so that we progress from -12, or spin the clock counterclockwise, which yields the same result.

Why don’t I number the clock starting with -1 and moving on to -2, etc? Because that would be moving backwards, continually decreasing until we hit -12, at which point we make a +12 jump, which isn’t how modulo works.

This Is a Known Thing

Before you think I’m nuts and start Googling on the subject: it’s been known for a while In fact, MDN (Mozilla Developer Network) goes so far as to call % the remainder operation:

The remainder operator returns the remainder left over when one operand is divided by a second operand. It always takes the sign of the dividend.

Eric Lippert, one of the gods of C#, says this about C#’s modulo:

However, that is not at all what the % operator actually does in C#. The % operator is not the canonical modulus operator, it is the remainder operator.

What does your language do?

So What?

I can understand if you’ve made it this far and are scratching your head some, wondering if you should care. I think you might want to for 2 specific reasons:

- I can see this coming up in an interview question, catching me completely off guard and

- I can see pushing a bug live and spinning for hours trying to figure out why math doesn’t work

It could also be a fun bit of trivia to keep in your pocket for when your pedantic programmer friend drops by.