Image credit: CCPixs.com

The first two posts in this series were philosophical musings on “why serverless” and “why not serverless”. With this post let’s write some code.

Rules…?

I was talking with Matthias Brandewinder recently at NDC Oslo. He does a lot of serverless stuff, but mostly with Azure Functions. One of the things we discussed was the absence of “patterns” for how to build things in a serverless environment.

Not the Gang of Four stuff - we were talking about architectural patterns. The question was a simple one:

Do we build things like we would otherwise? Or is there some type of pattern out there yet to be discovered?

I don’t know - and that’s kind of fun! I’ll ponder this question repeatedly as I add posts to this series. For now, let’s take the first step on our journey…

The First Function

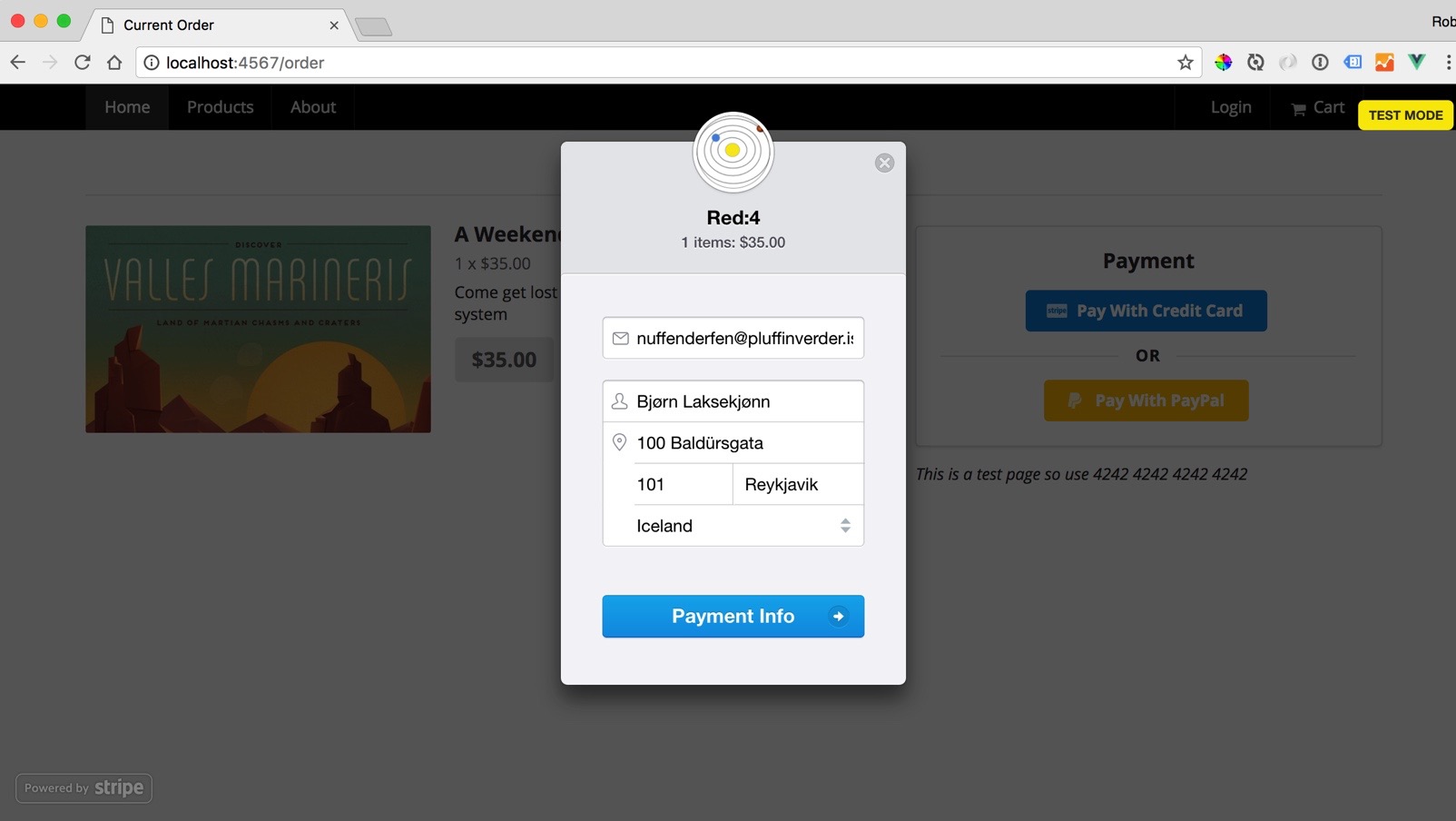

I’m building an ecommerce app, nothing terribly surprising about how it works. Product pages, a cart of some kind and finally a checkout page powered by Stripe:

This here is Stripe Checkout. You could write your own checkout form if you want, but I dig this.

Stripe works by sending the raw credit card/address information directly to Stripe, bypassing my app entirely. What I get back is a “token”, which is a reference to the checkout information stored on Stripe’s servers. I don’t want to go too deeply into all of this right now - have a look at their docs if you’re confused.

Once I have the token, I need to execute the charge. I’m not going to do this on the client, obviously, which makes this scenario perfect for Firebase functions.

To AJAX or Not?

Here is my Stripe configuration code:

var handler = StripeCheckout.configure({

key: 'MY PUBLIC KEY',

image: 'https://app.redfour.io/img/icon/apple-icon-180x180.png',

locale: 'auto',

zipCode: true,

billingAddress: true,

token: function(token) {

var payload = {

order: {

id: Cart.orderId, //RED4-20170622-k4kdls

processor: "stripe",

items: Cart.items

},

payment: token

};

//now what?

}

});

The token callback is the thing we’re most interested in. This is the code that fires once Stripe has processed and stored the user’s checkout information. Here I’m creating a payload, which has order information (including an order id, which is very important) and the order items. Finally I’m attaching the token, as that’s what we’ll use to capture the charge.

The question is: how do I get this to Firebase?

Option 1: Writing to the database

We know that Firebase functions are triggered off of events. The most logical one at this point is to use an “https event”, which is triggered when a specific URL is called. I could do that, or I could lean on Firebase completely by simply writing this payload directly:

firebase.database().ref(`sales/${Cart.orderId}/checkout`).set(payload);

This is using the browser-based firebase SDK to write my payload to the path specified. Notice how I’m using the Cart.orderId here? This serves two purposes:

- I can use it to define a path to a sale in the database

- I can use it to listen to a path to a sale in the database

This is where thinking in events starts to take shape! By writing this checkout information, we’ll be able to trigger a cascade of events that will, hopefully, culminate in a sale.

Problem: Security… Hello?

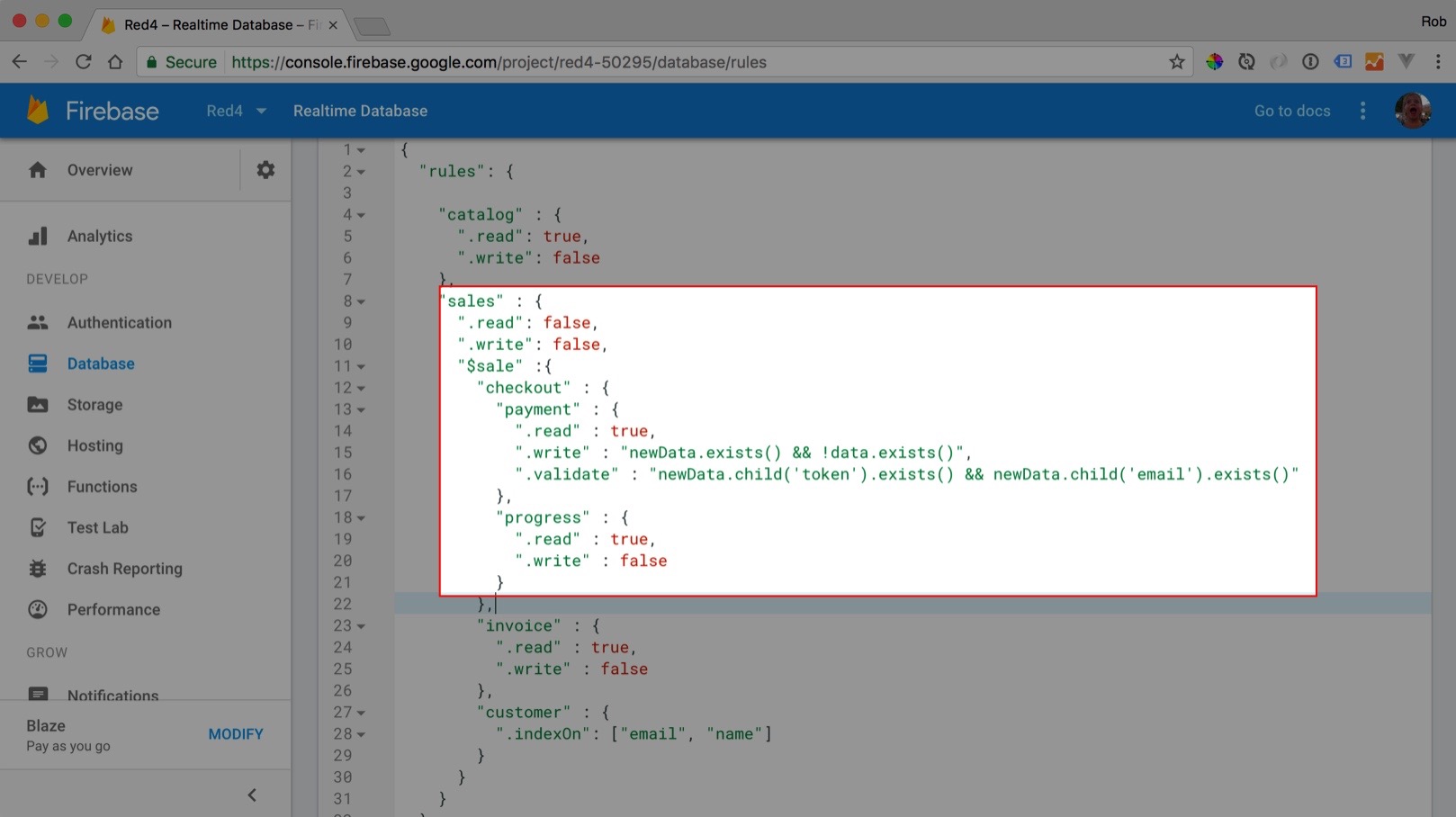

If you’re wondering if I’ve fallen and hit my head - I don’t blame you. Allowing the public to write to your database is completely lame! The good news is that we have some rules we can define to help us out. Let’s take a look at them now and I’ll explain more as we go:

Every firebase database allows you to specify a set of rules for working with data. These rules dictate what can be written, read, how to validate the data and finally how it should be indexed. I’ll get to all of this later on, for now, focus on the highlighted area.

I’m specifying rules for a given path using a JSON structure. This isn’t the easiest thing to get used to, but it only takes a few Googles to understand it. Here I’m specifying the path to the checkout data should be governed by a few conditions:

"sales" : {

".read": false,

".write": false,

"$sale" :{

"checkout" : {

"payment" : {

".read" : true,

".write" : "newData.exists() && !data.exists()",

".validate" : "newData.child('token').exists() && newData.child('email').exists()"

}

},

}

The first thing to notice is that rules cascade. At the very top I’m specifying that the public can’t read or write to the sales path. I’m overriding that on a per-sale basis by using $sale, which is a placeholder for every child of the parent sales key.

I override the parent read/write settings at the checkout/payment path, allowing reads, but only allowing writes when there’s new data and a record doesn’t already exist (newData and data are predefined variables). This will prevent people from changing their payment information.

Next, I have some simple validation, which ensures a token and email exist. By the way: if you’re wondering what the difference is between .validate and .write (as they basically do the same thing) - .validate does not cascade, which .write does.

Is this enough? Would your serverside code do more validation than this? You can build a pretty extensive validation expression here - it’s just JavaScript that gets eval’d every time a write happens.

Does It Matter?

Imagine you have a new CTO. Or maybe your company was just bought or transferred to a new division. You’re sitting in a code review and this new CTO (or tech manager, whatever) looks at your code and asks:

Let me get this straight… you’re letting the public write directly to the database?

Imagine if this meeting was taking place after an incident of some kind. It wouldn’t even need to be related to the checkout process. Heads will need to roll, and there’s very little you can say to get yourself out of this kind of jam.

Technically speaking, Firebase’s rules are pretty solid and you can do a number of things to mitigate bad guys. Politically speaking you might be putting a noose around your neck.

Your call.

Option 2: Make an AJAX Call

The easiest thing to do here is to just make an AJAX call:

var checkoutUrl = "https://some_firebase_function_url.com/stripe_charge";

$.ajax({

type: 'POST',

url: checkoutUrl,

data: payload,

dataType: 'json'

}).done(res => {

console.log(res)

}).fail(err => {

console.log(err);

});

This function will receive the payload, write it to the database and kick off the same cascade of events that you would otherwise. There are some other advantages as well:

- You can examine an IP address and stem flooding

- You can use anonymous authentication to do the same (which I’ll talk more about in a later post)

- You can write more comprehensive validation code

The downside to this is that these validations are in code at the app level, not nestled happily in front of the data. The best choice, probably, is to do a combination of the two things:

- Keep the validations discussed in Option 1, above

- Protect flooding using Option 2

Like I mention up top: there are no patterns here yet. This is all sort of new-ish, and this answer seems good to me.

Now What?

Now we get to write our receiver function - the entry point to our serverless backend. We’ll use an https triggered function to write the new order, and a further set of functions to process it both serially and concurrently.

We’ll do that in the next post.

See this series as a video

Watch how I built a serverless ecommerce site using Firebase. Over 3 hours of tightly-edited video, getting into the weeds with Firebase. We’ll use the realtime database, storage, auth, and yes, functions. I’ll also integrate Drip for user management. I detest foo/bar/hello-world demos; I want to see what’s really possible. That’s what this video is.