Arm-Waving

I find that when you discuss BDD or DDD a mix of jargon and definitions is thrown around until no one understands each other. This type of thing plagues software development (see REST) and makes it extremely difficult to discuss… well anything.

Behavior-driven Development, however, seems to be pretty straightforward as long as we adhere to the idea. But what is that idea and why does BDD exist in the first place?

Let’s start from the beginning - what problem are we solving. Here’s Dan North (the guy who created BDD):

… I kept coming across the same confusion and misunderstandings. Programmers wanted to know where to start, what to test and what not to test, how much to test in one go, what to call their tests, and how to understand why a test fails. The deeper I got into TDD, the more I felt that my own journey had been less of a wax-on, wax-off process of gradual mastery than a series of blind alleys.

I’ve felt the same way. If you’ve done TDD, it’s likely you’ve been very confused too. So how does BDD solve this stuff? Again, Dan:

I started using the word “behaviour” in place of “test” in my dealings with TDD and found that not only did it seem to fit but also that a whole category of coaching questions magically dissolved. I now had answers to some of those TDD questions. What to call your test is easy – it’s a sentence describing the next behaviour in which you are interested. How much to test becomes moot – you can only describe so much behaviour in a single sentence. When a test fails, simply work through the process described above – either you introduced a bug, the behaviour moved, or the test is no longer relevant.

I like it. You’re describing what your app does, not what it is (which is how TDD always felt to me). By focusing on what the app does you’re putting yourself in the user’s chair and this is critical.

Flexibility and Maintenance

In its simplest form, the classic definition of BDD asks you to:

- Define a story

- Create scenarios for that story

- Specify behaviors of your application for those scenarios

(I’ll be referring to this list repeatedly below)

That latter part is also called “Acceptance Criteria” and (this part is important) the acceptance criteria should be executable. This means that you can execute something that says “why yes, my application does behave this way”.

This approach is fantastic for a number of reasons, but the number one reason as far as I’m concerned is that you’re entire testing story is centered around Real World, Actual Use of your application! This keeps you focused on what’s important: User Happiness.

Another benefit here is that changing your tests around is mandated only when your application’s behavior changes. You can re-implement/refactor major chunks of your application but as long as you don’t change the behavior (which is usually the goal) - you don’t have a fleet of tests breaking.

This means that, over time, your tests remain nimble and flexible - meaning that changing things isn’t a massive headache. I like it.

Modern BDD And Confusion

BDD has changed over the years given the rise of specialized tools and frameworks. I like many of these tools - but you can still write Unit Tests with them, and indeed I think that’s what most people are doing.

Let’s take a look at a few modern examples of BDD starting with RSpec and the example found on the RSpec home page:

# bowling_spec.rb

require 'bowling'

describe Bowling, "#score" do

it "returns 0 for all gutter game" do

bowling = Bowling.new

20.times { bowling.hit(0) }

bowling.score.should eq(0)

end

end

This code seems pretty clear, but is there any behavior specified here? What I see is a Unit Test that is verifying the hit method increments a score attribute. Let’s take a look at another example from a BDD Game Kata

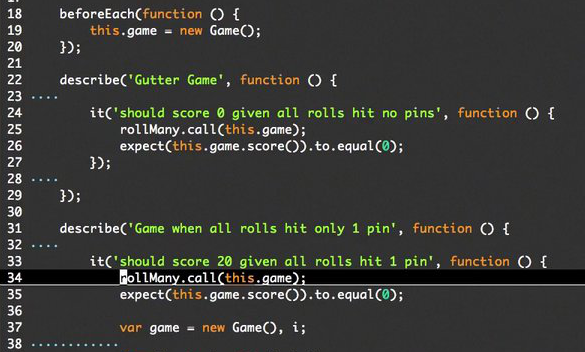

The wording is a bit different in this example and there’s a notion of a Game (this is Mocha and NodeJS) but what behaviors are under test is not clear. Once again - these tests are making sure that a score variable is set to 0 when 0 pins are knocked down.

So what’s the difference?

Focus On Behavior

I think all of these tests are valid, and all of these approaches work. But I think they don’t really fulfill Dan’s vision of “a story, with scenarios, that specify behavior”. Again: they work, but I think we could do better.

Let’s see how - and I’ll stick with the bowling context.

We’re trying to specify how our application will behave when something happens. In every example given so far, we don’t really know what we’re testing. In BDD you start with a “feature” and then think about that feature in terms of “scenarios”.

The feature it seems the above tests are focused on is Scoring. A scenario to consider is … no score at all! So how would we convey this with BDD? We could try something like this:

#bowling is not a feature of our application, scoring is

#and even then, scoring is different during and after - so let's be specific

describe "Final Scoring" do

#now we come up with a scenario

describe "No pins knocked down" do

#what happened?

it "is 0" do

#...

end

end

end

Just for fun let’s do this in XUnit and C# as well. We don’t have the descriptive ability that we do with RSpec - but we can put this in a file called “FinalScoring.cs” in a directory called “Scoring”:

[Trait("Scoring Completed Game", "No pins knocked down")]

public class NoPinsKnockedDown(){

[Fact(DisplayName="0 is the final score")]

public void ZeroIsFinalScore(){

//...

}

}

The difference here might seem subtle - and indeed it might seem like we’re testing the exact same code. But look again at the first example:

# bowling_spec.rb

require 'bowling'

describe Bowling, "#score" do

it "returns 0 for all gutter game" do

bowling = Bowling.new

20.times { bowling.hit(0) }

bowling.score.should eq(0)

end

end

How would you think differently about building your app if you had a suite of tests like this? Here we have the notion of Bowling as a model which has a method hit and an attribute of score. This doesn’t make much sense does it?

But this is “Model as Feature” way of testing that is fairly common with Rails.

Using a re-worded RSPec suite (my examples above) - you start to see the things that you would need to build in order to make this behavior happen. Different classes interacting that reflect the real world (and the problem at hand) present themselves much more readily.

Thinking In Scenarios

Let’s say you come over to my house one weekend and I share a beer that I made from a Super-Secret Recipe which I think you’ll love. You taste it and say “MMMMMMMMMM” and then you ask me more about the recipe.

I tell you some specifics RE temperature, hops additions and timing etc and, being a good Beer Geek you ask something along the lines of:

What would happen if you gave the bittering just 10 minutes more? And maybe did a hopback with a whirlpool and…

This is a natural dialog. I have an idea or concept and you want to question it so that a) you understand it better and b) you might help me improve it!

This is how BDD works too.

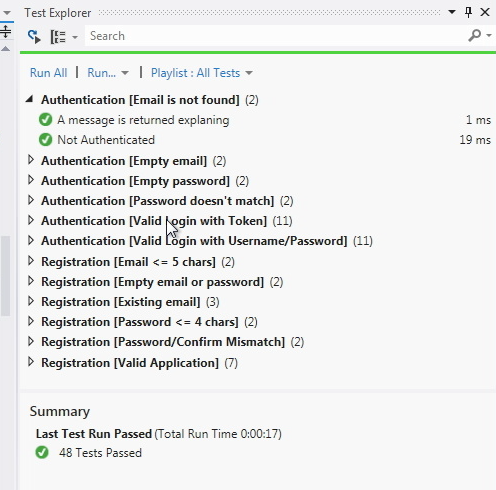

In Tekpub’s next video (where I work up a Membership library for .NET) I do exactly this: I have an idea, I lay out what should happen right up front, and then I think about all the different ways it can break :

I find that thinking in scenarios helps me tremendously because it’s a natural way we think. What you see in this screenshot above is XUnit written in the style of the examples above. I don’t believe that you need a specialized BDD framework to do BDD - just think in terms of “what happens to my app when I do this”.

The video should be out in a few weeks as we’re putting the final polish on it.